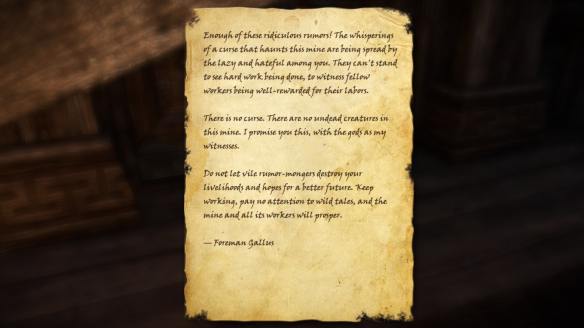

It is not possible to live a normal life when your country is at war, even when the fighting is far away. For the people of Cyrodiil it is not necessarily the fighting amongst the invading Banner’s that they fear the most, but the consequences of their fighting; the anarchy that is no longer controlled, the bandits, wild beasts, daedra, and risen dead that are no longer kept in check. At the Waterside Mine for example, I discover the site deserted and littered with the bodies of dead miners. Quickly however I discover that the fallen are not so lifeless after-all, and as I approach the bodies, they twitch, rise and attack.

I suspect that in more peaceful times at the first sign of the undead a squad would have been sent out from the nearby Drakelowe Keep, and the problem would have been dealt with by the Legions long before the entire mine was lost. Once the people of Cyrodiil could live relatively safe lives, perhaps even enjoying the luxury of grumbling about the strict, heavy-handed, uncivil legionnaires that restrict their freedoms, because their freedoms were protected by those strict, heavy-handed, uncivil legionnaires. But now there are no Legions to protect the province, there is no one to confront violence on their behalf, and faith alone is neither shield nor weapon. How long can they rely upon passing mercenaries and adventurers? If the people of Cyrodiil are to survive this war, they must learn quickly how to defend themselves.

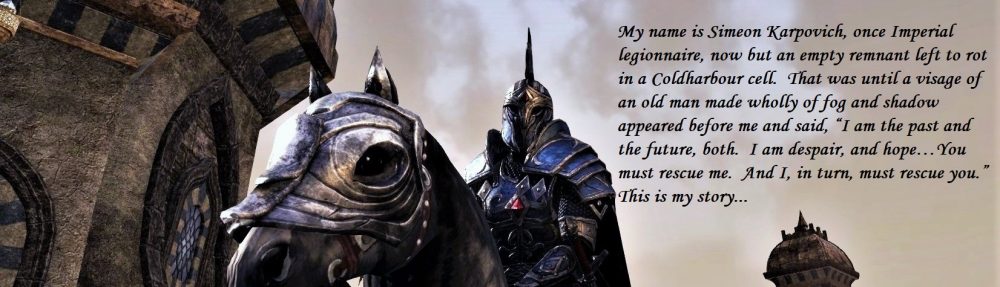

S.K